Remarks On George Marshall and the Foundations of Smart Power

Remarks

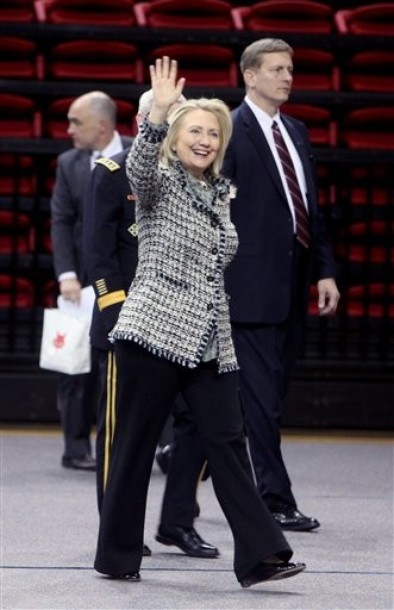

Hillary Rodham Clinton

Secretary of State

Virginia Military Institute, Cameron Hall

Lexington, VA

April 3, 2012

Thank

you. Thank you very much for welcoming me to VMI, and thanks especially

to all the cadets – to those of you who aspire to serve our country as

members of the military, or as entrepreneurs and engineers; as teachers

and doctors; as development experts and maybe even a few Foreign Service

officers. Each of you represents VMI’s commitment to the common good

and you build on a long tradition of service.

Let me express my

thanks to General Peay, Brigadier General Green, Brigadier General

Schneiter, Colonel Hentz, and all of VMI’s leadership for stewarding one

of our nation’s finest and most historic educational institutions.

I

was telling the leadership team before I came in that I grew up next

door outside of Chicago, Illinois in a suburb to a family that was

headed by a VMI graduate, and so I heard about VMI from a very early

age. And I often thought about my friend and neighbor and his son, who

also went to VMI, someone who I went all through school with, and how

proud they were to say that they had graduated. And for me, that is

understandable because VMI has trained some our country’s most

distinguished leaders. It is, as you know, one of the largest producers

of commissioned officers to the United States military and the only

military college whose graduates have led three of the four services –

the Army, the Air Force, and the Marine Corps twice.

So it is a

great personal honor to be receiving the Distinguished Diplomat Award

from such a fine institution and to follow in the footsteps of those who

have come before, and in particular, to be here on a campus that

nurtured one of the greatest Americans of all time.

Now, I am sure

you’re used to speakers coming here and singing the praises of George

Marshall as both a soldier and a statesman, his integrity and valor, his

selflessness and loyalty, his honesty. But one of my favorite stories

about George Marshall comes from before the time his name was written in

every American history book.

The story goes that when he first

arrived at VMI, no one expected he would achieve very much at all. He

was shy. He was scared. He was awkward and a rather mediocre student.

Many

years later, General Marshall was asked what changed him. And he told a

story about overhearing his older brother, also a VMI cadet, warning

their mother that George was so weak and timid that he would “disgrace

the family name” at VMI. And George Marshall said, “I decided right then

and there that I was going to wipe his eye.” Overhearing that

conversation sparked what he later called an “urgency to succeed.”

Now,

I suspect we can all examine our lives and relate to that feeling

Marshall was talking about – that urge to channel our doubts and

uncertainty into a call to be better and stronger. And on a larger

level, we can apply that lesson to our institutions and our society as

we face this new age of challenges. Marshall’s contributions as

Secretary of State did not come just from that urgency to succeed or

from his courage and integrity. They really came from his vision of

American strength and American leadership – a vision that was both

perfectly suited to his time and far ahead of it.

Now, some of you

may have heard that I like to talk about the Three Ds of foreign policy

– the need to elevate diplomacy and development alongside defense as

pillars of our national security. Well, George Marshall was the original

Three D guy. Just by taking on the job of Secretary of State after a

lifetime of military service and leadership, Marshall sent a message

about the strong links between diplomacy and defense.

Now, of

course, not everyone saw the connection. After World War II, many

Americans wanted to withdraw from the world. They believed that strong

defenses would be enough to keep us safe. But General Marshall knew even

then that the world’s most powerful military was not sufficient to

ensure our security on its own.

And make no mistake about it:

American military strength still underwrites our exceptional leadership

around the world today, as it did then. But here’s what Marshall said in

his farewell speech from the Army: “Along with the great problem of

maintaining the peace, we must solve the problem of the pittance of

food, of clothing and coal and homes. Neither of these problems can be

solved alone. They are directly related to one another.”

Well,

that was a recognition that advancing our own interests depends on

improving the conditions in which other human beings around the world

live. George Marshall believed that to guarantee our own security, we

had to draw on all the tools of our power. And that has never been truer

than today. Once again, our country is facing tight budgets, and there

is a dangerous impulse to withdraw from our responsibilities, because,

some say, we can no longer afford to engage internationally. But now, as

then, we must recognize that strengthening America’s global leadership

is the best investment we can make in our own future.

So that’s

why we are pursuing a foreign policy built on the three Ds, a strategy

that updates Marshall’s vision and applies it to the globalized world of

the 21st century. When Marshall looked at a Europe shattered

by war, he knew that hunger and poverty would ultimately undermine our

own prosperity and opportunity, that desperation and chaos would

ultimately give rise to forces that would threaten us here at home. And

today, we can see the truth of those insights in so many ways. We see

how some of the greatest threats to our security come from a lack of

opportunity, the denial of human rights, a changing climate, strains on

water, food, and energy.

We see how resolving today’s conflicts

depends on fostering economic development, good governance, the rule of

law, alongside our military efforts. And just like George Marshall in

his day, our military leaders have made some of the loudest calls for

elevating diplomacy and development alongside defense. To cite just one

example, when Leon Panetta became Secretary of Defense last year, he

stressed the importance of this integrated approach right off the bat.

He said national security is dependent on a number of factors. It’s

dependent on strong diplomacy, it’s dependent on our ability to reach

out and try to help other countries, it’s dependent on our ability to

try to do what we can to inspire development. So we have worked hand in

hand with our military colleagues to build a foreign policy based on

smart power for the 21st century, a foreign policy that

produces results for global peace, prosperity, and progress, all of

which are profoundly in America’s interests.

Let me briefly

explain how we are putting this vision of smart power into action.

First, we are bringing all the tools of American power to bear in

conflict and post-conflict situations, where the links among defense,

diplomacy, and development are the most obvious. Think Afghanistan,

Iraq, fighting the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda and elsewhere in

Africa, protecting civilians while helping support the creation of a new

Libya. Security improvements only last when they are backed by

effective, accountable governments that can deliver results for their

people. And building up those governments and their institutions

requires a strong and active civilian presence.

In Afghanistan,

for example, we are pursuing a three-part approach that we call fight,

talk, build. And this is 3-D security in action. Our military is

maintaining pressure on the Taliban to come to the negotiating table and

enhancing the security capabilities of the Afghan forces. At the same

time, we are opening the door for Afghans to engage in an inclusive

peace process that could separate the Taliban from al-Qaida and end

decades of conflict in Afghanistan. And finally, we are working to lay

an economic foundation for long-term, sustainable development.

These

three prongs of fight, talk, and build are mutually reinforcing and

crucial to strengthening and building on the gains the Afghan people

have made over the past decade, from crucial advancements in women’s

rights to enhanced access to basic medical care and education for girls

and boys. Without a doubt, this has been a particularly difficult period

in our relationship with Afghanistan, and there are enormous challenges

ahead. Even as we move toward the end of our security transition in

2014, the United States will continue working with the Afghan people to

help build a better future. And in the next month, we hope to finalize a

Strategic Partnership Agreement between the United States and

Afghanistan, which makes our long-term commitment clear. We know that we

cannot abandon Afghanistan without paying the price as we have in the

past. So we think it is definitely in our interest to help continue

moving Afghanistan toward self-sufficiency and establishing lasting

security.

In Iraq, we have completed the largest transition from

military to civilian leadership since the Marshall Plan. Civilians are

leading our lasting partnership with a free and democratic Iraq. Now we

are very clear-eyed about the challenges that remain and the work that

lies ahead. But Iraq has taken charge of its own security and has the

chance, if its leaders take it, to stand as an important example of an

emerging democracy in a region experiencing historic transformation.

This

time last year, we stepped up with military and civilian support in

Libya’s hour of need. But the true measure of Libya’s success will not

be in toppling a dictator, but in building a democracy based on the rule

of law and respect for human rights.

And our troops and civilians

are working together in other places as well. Long before the Kony 2012

campaign made the Lord’s Resistance Army a popular topic of discussion,

we had soldiers and civilians on the ground, working to help

communities address this threat. When a devastating earthquake and

tsunami hit Japan last year, our military forces, diplomats, and

development experts pulled together to deliver a massive and immediate

response. And in the Horn of Africa, the United States has provided

almost $1 billion in humanitarian assistance that has saved countless

lives from malnutrition, starvation, and disease. And our sustained

commitment has demonstrated the best of America, helping to undermine

the extremist narrative of terrorist groups like al-Shabaab in Somalia.

So

our military and civilian forces, working alongside one another in many

places, experience immediate conflict and crisis. But we also work

together to try to reduce the number of places where we need to have

that kind of response, because sending American soldiers, sailors,

airmen and Marines into harm’s way is not a decision that any president

makes lightly. So at the State Department, our diplomats work around the

clock to do everything we can to exhaust all other options. So a second

key element of our smart power agenda is using diplomacy to prevent

conflicts and resolve disputes before they become crises that could

demand military intervention.

Let’s look at one prominent example

from the headlines: our ongoing efforts to apply international pressure

on the Iranian regime. Now President Obama has made it clear that he is

determined to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons and that all

options remain on the table. But we believe there is still time and

space for sanctions and diplomacy to work.

So we are preparing for

another round of what’s called the P-5+1 talks – those are the

permanent members of the Security Council: the United States, United

Kingdom, France, Russia, and China, along with Germany and the European

Union – for talks later this month, but not an open-ended session for

both parties to talk around each other without ever coming to any

agreement. We expect to see concrete commitments from Iran that it will

come clean on its nuclear program and live up to its international

obligations.

And in the meantime, we are maintaining a full-court

press against the regime, enforcing the most comprehensive package of

sanctions in history and further isolating Iran from the international

community. This sustained pressure is bringing Iran’s leaders back to

the negotiating table, and we hope that it will result in a plan of

action that will resolve our disagreements peacefully.

Working

hand in hand with our diplomacy efforts, the third D of smart power is

development: investing in the long-term foundations of human security

and stability. Now of course, our development work is rooted in our

values. We think it’s wrong that people die of preventable diseases and

conditions that have no place in the 21st century. But

development is also an essential and equal pillar of our national

security strategy. We want to help countries become more self-sufficient

so they can be stronger partners to help us take on shared challenges.

Broad based economic growth fosters human dignity and helps build more

stable societies.

And not only research, but human experience,

suggests that as many as 40 percent of countries recovering from

conflict revert to violence within a decade. But when they grow their

economies and raise people’s income, the risk of violence drops

substantially. And there is no better way of doing that than introducing

free-market principles, encouraging entrepreneurship, creating

conditions for men and women to see the results of their own labor in

rising incomes and better opportunities for their children.

Now,

when we look at development, we start with the basics. What do we want

in our lives? Because it’s not so different from what others seek. When a

child dies from hunger every six seconds in the world, we want to do

more to make sure mothers and children get enough to eat, especially

during that 1,000 day window from pregnancy to two years old when

malnutrition can permanently undermine a child’s development.

So

our Feed the Future initiative is helping countries develop their own

plans to improve agricultural output. In order for children to get

enough to eat, farmers need enough to sell, and families should not have

to worry where their next meal comes from. So our goal is not just to

intervene in crises, like famines, but to try to help farmers improve

their own yield. We’re looking for that day when countries no longer

require outside aid to nourish their own people. And we also want to

avoid conflicts over food resources, and foster a stronger, more

productive population in our partner nations.

Our Global Health

Initiative treats diseases while improving health systems because we

want countries to take more responsibility for delivering health care to

their own people. So that may mean in some places working to curb

tuberculosis or other neglected tropical diseases, providing life-saving

HIV treatment for 6 million people by the end of next year to lay the

foundation for an AIDS-free generation. By working to really listen to

the desires of other countries and bring them to the table as partners,

we can actually accomplish more with the same resources.

And one

particular principle throughout these programs is our focus on women and

girls. Why? Because experience and, again, piles of evidence show that

if we want to expand economic opportunity and growth, improve national

health and education, promote responsible governance and democracy, we

need to involve women at every step. And here at VMI – (applause) – in

the 15 years since female cadets joined the ranks and the ratline at

VMI, I think you’ve seen how women have made unique contributions to

strengthen and honor this institution. We simply cannot leave half the

population behind anywhere if we’re going to make progress together.

So

using these principles of smart power, we are working with our military

to support security gains and foster long-term stability, to solve

problems and defuse crisis situations, and we are emphasizing

development as a means to prevent conflict from taking root over the

long term. And we recognize that in order to deploy these tools of smart

power at this time, we have to reflect and respond to the dramatic

global changes that are sweeping the world and that have changed the way

we have to do business.

So we’ve taken a hard look at the

structure of the State Department and USAID. We’ve taken a look at our

approach and our basic capabilities. Now, some of you may have heard of

the Quadrennial Defense Review. That’s the Department of Defense’s

effort every four years to align its resources and organization with its

strategies and demands. I saw firsthand how effective the QDR was when I

served on the Senate Armed Services Committee, so we stole that idea

for the State Department. And in December 2010, we released the

first-ever Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review – the QDDR.

And

since then, we have worked to break down the silos that too often build

up between offices and agencies, to equip ourselves to deal with the

long-term global trends. For example, when I arrived at the State

Department, I realized that energy security was certainly one of the

defining challenges of our time. So I created a new bureau in the State

Department filled with experts and diplomats who lead our government’s

work to ensure a stable, affordable supply of energy as we transition

over time to a clean energy economy.

We also improved our focus on

the essential elements of building democratic, secure, and just

societies. And our counterterrorism and law enforcement programs are now

housed side by side with those that defend human rights and promote

opportunities for young people. Our new Bureau of Conflict and

Stabilization Operations is working to improve our ability to prevent

violent conflict and respond when crises break out. And we’re

strengthening our leadership and our Civilian Response Corps to make it

more flexible and expeditionary.

Today’s civilian experts are as

likely to wear work boots and cargo pants as business suits and loafers.

They function in some of the most remote and least governed places on

the planet. They work as a unified force – development experts,

agricultural specialists, democracy and human rights advocates – to

advance America’s core interests.

Now, part of doing business

differently means using new tools to engage more people in more places,

and reaching beyond governments to talk directly to people. This is what

we call 21st century statecraft. So our ambassadors are now

blogging, and yes, tweeting. Every embassy has a Facebook page. And

we’re doing more than just talking. We’re listening and hearing from

communities we’ve never been able to reach before.

You saw some of

that in this past year. After Mubarak stepped down and as Egyptians

were beginning to grapple with tough questions about what next, I

participated in a virtual town hall with Egyptian youth. And from my

office in Washington, I took questions online from across Egypt. And

they asked tough questions, and it was a vigorous exchange. Many,

honestly, were critical of the United States and they were not afraid to

say so. But just the act of talking honestly and openly with one

another was revolutionary and gives us the chance to build new

relationships. I’ve done the same with people from Iran, doing online

talks that were immediately translated into Farsi, and hearing from

people inside Iran about the challenges and the hopes and aspirations

that they feel for themselves. So these are all smart power concerns,

central to core national security.

Now, some Americans may

question how rebuilding economies helps us respond to the biggest

threats we face, and whether development aid is diverting money that

would be better spent at home. Well, George Marshall heard these same

concerns. I can remember reading about the Marshall Plan and just

thinking how unlikely it was, after men like my father, who served in

the Navy during World War II, came home, and all they wanted to do was

just build a normal life, get back to business, raise a family, buy a

house. And Marshall knew that, but he didn’t listen to the skeptics. He

held fast to his vision. And he barnstormed around the country, along

with others, to help build the understanding and the alliance that would

build those enemies that just a short time before he and people like my

father had been doing everything they could to defeat, because he

understood that in order for America to have peace and prosperity, we

have to invest in that potential for others.

As Americans look out

on a global landscape of growing complexity with new powers and new

challenges, we have to hold fast to that same vision. Our foreign policy

can’t succeed unless it has the full support of the American people.

And certainly, as we think about all those World War II veterans who

came home and were told, you know what, you’re going to have to keep

paying taxes, and a huge amount of that money is going to rebuild those

very countries that we tried to destroy, well, can you imagine that

argument today? Somebody stands up and says, “We need to tax you more to

rebuild another country somewhere else.” I can imagine what would be

said on talk radio and cable television. And it took a great

citizen-soldier, a VMI cadet, to make the case for smart power then.

Well, I think it will take your generation of citizen-soldiers to make the case for smart power in the 21st

century. Our American values – honor, duty, and sacrifice, freedom,

compassion, humility – are a great source of our global strength and

pride. And we look to each of you as you live these values and continue

in your careers to make your contribution to our country and to help

show the American people why our national security depends on human

security, to prove that once again, American leadership makes us all

safer when we promote dignity and opportunity everywhere.

I’m very

excited about what the future holds. I agree that the world in some

ways was simpler when we had a bipolar world with a clear dividing line

between the United States and freedom, and the Soviet Union and others

and communism. So yes, it’s more complicated. The problems are

multipolar. But America’s strength is still necessary. We cannot solve

all the problems in the world, but there is no big problem that can be

solved without us.

So I thank you for your commitment to

citizenship and to service, to your commitment to building your own

lives and futures, to have that urgency to succeed, not only for

yourselves but for this great nation that we love and cherish.

Thank you very much. (Applause.)