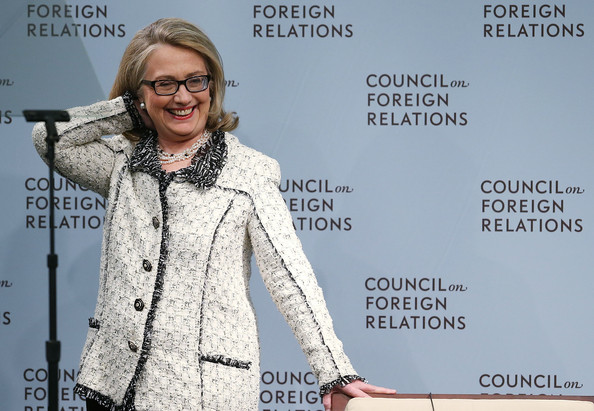

Remarks on American Leadership at the Council on Foreign Relations

Remarks

Hillary Rodham Clinton

Secretary of StateWashington, DCJanuary 31, 2013

SECRETARY CLINTON: Thank you, Richard, for that introduction and for everything you’ve done to lead this very valuable institution. I also want to thank the board of the Council on Foreign Relations and all my friends and colleagues and other interested citizens who are here today, because you respect the Council, you understand the important work that it does, and you are committed to ensuring that we chart a path to the future that is in the best interests not only of the United States, but of the world.

As Richard said, tomorrow is my last day as Secretary of State. And though it is hard to predict what any day in this job will bring, I know that tomorrow, my heart will be very full. Serving with the men and women of the State Department and USAID has been a singular honor. And Secretary Kerry will find there is no more extraordinary group of people working anywhere in the world. So these last days have been bittersweet for me, but this opportunity that I have here before you gives me some time to reflect on the distance that we’ve traveled, and to take stock of what we’ve done and what is left to do.

I think it’s important, as Richard alluded in his opening comments, what we faced in January of 2009: Two wars, an economy in freefall, traditional alliances fraying, our diplomatic standing damaged, and around the world, people questioning America’s commitment to core values and our ability to maintain our global leadership. That was my inbox on day one as your Secretary of State.

Today, the world remains a dangerous and complicated place, and of course, we still face many difficult challenges. But a lot has changed in the last four years. Under President Obama’s leadership, we’ve ended the war in Iraq, begun a transition in Afghanistan, and brought Usama bin Ladin to justice. We have also revitalized American diplomacy and strengthened our alliances. And while our economic recovery is not yet complete, we are heading in the right direction. In short, America today is stronger at home and more respected in the world. And our global leadership is on firmer footing than many predicted.

To understand what we have been trying to do these last four years, it’s helpful to start with some history.

Last year, I was honored to deliver the Forrestal Lecture at the Naval Academy, named for our first Secretary of Defense after World War II. In 1946, James Forrestal noted in his diary that the Soviets believed that the post-war world should be shaped by a handful of major powers acting alone. But, he went on, “The American point of view is that all nations professing a desire for peace and democracy should participate.”

And what ended up happening in the years since is something in between. The United States and our allies succeeded in constructing a broad international architecture of institutions and alliances – chiefly the UN, the IMF, the World Bank, and NATO – that protected our interests, defended universal values, and benefitted peoples and nations around the world. Yet it is undeniable that a handful of major powers did end up controlling those institutions, setting norms, and shaping international affairs.

Now, two decades after the end of the Cold War, we face a different world. More countries than ever have a voice in global debates. We see more paths to power opening up as nations gain influence through the strength of their economies rather than their militaries. And political and technological changes are empowering non-state actors, like activists, corporations, and terrorist networks.

At the same time, we face challenges, from financial contagion to climate change to human and wildlife trafficking, that spill across borders and defy unilateral solutions. As President Obama has said, the old postwar architecture is crumbling under the weight of new threats. So the geometry of global power has become more distributed and diffuse as the challenges we face have become more complex and crosscutting.

So the question we ask ourselves every day is: What does this mean for America? And then we go on to say: How can we advance our own interests and also uphold a just, rules-based international order, a system that does provide clear rules of the road for everything from intellectual property rights to freedom of navigation to fair labor standards?

Simply put, we have to be smart about how we use our power. Not because we have less of it – indeed, the might of our military, the size of our economy, the influence of our diplomacy, and the creative energy of our people remain unrivaled. No, it’s because as the world has changed, so too have the levers of power that can most effectively shape international affairs.

I’ve come to think of it like this: Truman and Acheson were building the Parthenon with classical geometry and clear lines. The pillars were a handful of big institutions and alliances dominated by major powers. And that structure delivered unprecedented peace and prosperity. But time takes its toll, even on the greatest edifice.

And we do need a new architecture for this new world; more Frank Gehry than formal Greek. (Laughter.) Think of it. Now, some of his work at first might appear haphazard, but in fact, it’s highly intentional and sophisticated. Where once a few strong columns could hold up the weight of the world, today we need a dynamic mix of materials and structures.

Now, of course, American military and economic strength will remain the foundation of our global leadership. As we saw from the intervention to stop a massacre in Libya to the raid that brought bin Ladin to justice, there will always be times when it is necessary and just to use force. America’s ability to project power all over the globe remains essential. And I’m very proud of the partnerships that the State Department has formed with the Pentagon, first with Bob Gates and Mike Mullen and then with Leon Panetta and Marty Dempsey.

By the same token, America’s traditional allies and friends in Europe and East Asia remain invaluable partners on nearly everything we do. And we have spent considerable energy strengthening those bonds over the past four years.

And, I would be quick to add, the UN, the IMF, the World Bank, and NATO are also still essential. But all of our institutions and our relationships need to be modernized and complemented by new institutions, relationships, and partnerships that are tailored for new challenges and modeled to the needs of a variable landscape, like how we elevated the G-20 during the financial crisis, or created the Climate and Clean Air Coalition out of the State Department to fight short-lived pollutants like black carbon, or worked with partners like Turkey, where the two of us stood up the first Global Counterterrorism Forum.

We’re also working more than ever with invigorated regional organizations. Consider the African Union in Somalia and the Arab League in Libya, even sub-regional groups like the Lower Mekong Initiative that we created to help reintegrate Burma into its neighborhood and try to work across national boundaries on issues like whether dams should or should not be built.

We’re also, of course, thinking about old-fashioned shoe-leather diplomacy in a new way. I have found it, and I’ve said this before, highly ironic that in today’s world, when we can be anywhere virtually, more than ever, people want us to actually show up. But while a Secretary of State in an earlier era might have been able to focus on a small number of influential capitals, shuttling between the major powers, today we, by necessity, must take a broader view.

And people say to me all the time, “I look at your travel schedule; why Togo?” Well, no Secretary of State had ever been to Togo. But Togo happens to hold a rotating seat on the UN Security Council. Going there, making the personal investment has a strategic purpose.

And it’s not just where we engage, but with whom. You can’t build a set of durable partnerships in the 21st century with governments alone. The opinions of people now matter as to how their governments work with us, whether it’s democratic or authoritarian. So in virtually every country I have visited, I’ve held town halls and reached out directly to citizens, civil society organizations, women’s groups, business communities, and so many others. They have valuable insights and contributions to make. And increasingly, they are driving economic and political change, especially in democracies.

The State Department now has Twitter feeds in 11 languages. And just this Tuesday, I participated in a global town hall and took questions from people on every continent, including, for the first time, Antarctica.

So the point is: We have to be strategic about all the levers of global power and look for the new levers that could not have been possible or had not even been invented a decade ago. We need to widen the aperture of our engagement, and let me offer a few examples of how we’re doing this.

First, technology. You can’t be a 21st century leader without 21st century tools, not when people organize pro-democracy protests with Twitter and while terrorists spread their hateful ideology online. That’s why I have championed what we call 21st century statecraft.

We’ve launched an interagency Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications at State. Experts, tech-savvy specialists from across our government fluent in Urdu, Arabic, Punjabi, Somali, use social media to expose al-Qaida’s contradictions and abuses, including its continuing brutal attacks on Muslim civilians.

We’re leading the effort also to defend internet freedom so it remains a free, open, and reliable platform for everyone. We’re helping human rights activists in oppressive internet environments get online and communicate more safely. Because the country that built the internet ought to be leading the fight to protect it from those who would censor it or use it as a tool of control.

Second, our nonproliferation agenda. Negotiating the New START Treaty with Russia was an example of traditional diplomacy at its best. Then working it through the Congress was an example of traditional bipartisan support at its best. But we also have been working with partners around the world to create a new institution, the Nuclear Security Summit, to keep dangerous materials out of the hands of terrorists. We conducted intensive diplomacy with major powers to impose crippling sanctions against Iran and North Korea. But to enforce those sanctions, we also enlisted banks, insurance companies, and high-tech international financial institutions. And today, Iran’s oil tankers sit idle, and its currency has taken a massive hit.

Now, this brings me to a third lever: economics. Everyone knows how important that is. But not long ago, it was thought that business drove markets and governments drove geopolitics. Well, those two, if they ever were separate, have certainly converged.

So creating jobs at home is now part of the portfolio of diplomats abroad. They are arguing for common economic rules of the road, especially in Asia, so we can make trade a race to the top, not a scramble to the bottom. We are prioritizing economics in our engagement in every region, like in Latin America, where, as you know, we ratified free trade agreements with Colombia and Panama.

And we’re also using economic tools to address strategic challenges, for example, in Afghanistan, because along with the security transition and the political transition, we are supporting an economic transition that boosts the private sector and increases regional economic integration. It’s a vision of transit and trade connections we call the New Silk Road.

A related lever of power is development. And we are helping developing countries grow their economies not just through traditional assistance, but also through greater trade and investment, partnerships with the private sector, better governance, and more participation from women. We think this is an investment in our own economic future. And I love saying this, because people are always quite surprised to hear it: Seven of the 10 fastest growing economies in the world are in Africa. Other countries are doing everything they can to help their companies win contracts and invest in emerging markets. Other countries still are engaged in a very clear and relentless economic diplomacy. We should too, and increasingly, we are.

And make no mistake: There is a crucial strategic dimension to this development work as well. Weak states represent some of our most significant threats. We have an interest in strengthening them and building more capable partners that can tackle their own security problems at home and in their neighborhoods, and economics will always play a role in that.

Next, think about energy and climate change. Managing the world’s energy supplies in a way that minimizes conflict and supports economic growth while protecting the future of our planet is one of the greatest challenges of our time.

So we’re using both high-level international diplomacy and grassroots partnerships to curb carbon emissions and other causes of climate change. We’ve created a new bureau at the State Department focused on energy diplomacy as well as new partnerships like the U.S.-EU Energy Council. We’ve worked intensively with the Iraqis to support their energy sector, because it is critical not only to their economy, their stability as well. And we’ve significantly intensified our efforts to resolve energy disputes from the South China Sea to the eastern Mediterranean to keep the world’s energy markets stable. Now this has been helped quite significantly by the increase in our own domestic production. It’s no accident that as Iranian oil has gone offline because of our sanctions, other sources have come online, so Iran cannot benefit from increased prices.

Then there’s human rights and our support for democracy and the rule of law, levers of power and values we cannot afford to ignore. In the last century, the United States led the world in recognizing that universal rights exist and that governments are obligated to protect them. Now we have placed ourselves at the frontlines of today’s emerging battles, like the fight to defend the human rights of the LGBT communities around the world and religious minorities wherever and whoever they are. But it’s not a coincidence that virtually every country that threatens regional and global peace is a place where human rights are in peril or the rule of law is weak.

More specifically, places where women and girls are treated as second-class, marginal human beings. Just ask young Malala from Pakistan. Ask the women of northern Mali who live in fear and can no longer go to school. Ask the women of the Eastern Congo who endure rape as a weapon of war.

And that is the final lever that I want to highlight briefly. Because the jury is in, the evidence is absolutely indisputable: If women and girls everywhere were treated as equal to men in rights, dignity, and opportunity, we would see political and economic progress everywhere. So this is not only a moral issue, which, of course, it is. It is an economic issue and a security issue, and it is the unfinished business of the 21st century. It therefore must be central to U.S. foreign policy.

One of the first things I did as Secretary was to elevate the Office of Global Women’s Issues under the first Ambassador-at-Large, Melanne Verveer. And I’m very pleased that yesterday, the President signed a memorandum making that office permanent.

In the past four years, we’ve made – (applause) – thank you. In the past four years, we’ve made a major push at the United Nations to integrate women in peace and security-building worldwide, and we’ve seen successes in places like Liberia. We’ve urged leaders in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya to recognize women as equal citizens with important contributions to make. We are supporting women entrepreneurs around the world who are creating jobs and driving growth.

So technology, development, human rights, women. Now, I know that a lot of pundits hear that list and they say: Isn’t that all a bit soft? What about the hard stuff? Well, that is a false choice. We need both, and no one should think otherwise.

I will be the first to stand up and proclaim loudly and clearly that America’s military might is and must remain the greatest fighting force in the history of the world. I will also make very clear, as I have done over the last years, that our diplomatic power, the ability to convene, our moral suasion is effective because the United States can back up our words with action. We will ensure freedom of navigation in all the world’s seas. We will relentlessly go after al-Qaida, its affiliates, and its wannabes. We will do what is necessary to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon.

There are limits to what soft power on its own can achieve. And there are limits to what hard power on its own can achieve. That’s why, from day one, I’ve been talking about smart power. And when you look at our approach to two regions undergoing sweeping shifts, you can see how this works in practice.

First, America’s expanding engagement in the Asia Pacific. Now, much attention has been focused on our military moves in the region. And certainly, adapting our force posture is a key element of our comprehensive strategy. But so is strengthening our alliances through new economic and security arrangements. We’ve sent Marines to Darwin, but we’ve also ratified the Korea Free Trade Agreement. We responded to the triple disaster in Japan through our governments, through our businesses, through our not-for-profits, and reminded the entire region of the irreplaceable role America plays.

First and foremost, this so-called pivot has been about creative diplomacy:

Like signing a little-noted treaty of amity and cooperation with ASEAN that opened the door to permanent representation and ultimately elevated a forum for engaging on high-stakes issues like the South China Sea. We’ve encouraged India’s “Look East” policy as a way to weave another big democracy into the fabric of the Asia Pacific. We’ve used trade negotiations over the Trans-Pacific Partnership to find common ground with a former adversary in Vietnam. And the list goes on. Our effort has encompassed all the levers of powers and more that I’ve both discussed and that we have utilized.

And you can ask yourself: How could we approach an issue as thorny and dangerous as territorial disputes in the South China Sea without a deep understanding of energy politics, subtle multilateral diplomacy, smart economic statecraft, and a firm adherence to universal norms?

Or think about Burma. Supporting the historic opening there took a blend of economic, diplomatic, and political tools. The country’s leaders wanted the benefits of rejoining the global economy. They wanted to more fully participate in the region’s multilateral institutions and to no longer be an international pariah. So we needed to engage with them on many fronts to make that happen, pressing for the release of political prisoners and additional reforms while also boosting investment and upgrading our diplomatic relations.

Then there’s China. Navigating this relationship is uniquely consequential, because how we deal with one another will define so much of our common future. It is also uniquely complex, because – as I have said on many occasions, and as I have had very high-level Chinese leaders quote back to me – we are trying to write a new answer to the age-old question of what happens when an established power and a rising power meet.

To make this work, we really do have to be able to use every lever at our disposal all the time. So we expanded our high-level engagement through the Strategic & Economic Dialogue to cover both traditional strategic issues like North Korea and maritime security, and also emerging challenges like climate change, cyber security, intellectual property concerns, as well as human rights.

Now, this approach was put to the test last May when we had to keep a summit meeting of the dialogue on track while also addressing a crisis over the fate of a blind human rights dissident who had sought refuge in our American Embassy. Not so long ago, such an incident might very well have scuttled the talks. But we have though intense effort, confidence building, we have built enough breadth and resilience into the relationship to be able to defend our values and promote our interests at the same time.

We passed that test, but there will be others. The Pacific is big enough for all of us, and we will continue to welcome China’s rise – if it chooses to play a constructive role in the region. For both of us, the future of this relationship depends on our ability to engage across all these issues at once.

That’s true as well for another complicated and important region: the Middle East and North Africa.

I’ve talked at length recently about our strategy in this region, including in speeches at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Saban Forum, and in my recent testimony before Congress. So let me just say this.

There has been progress: American soldiers have come home from Iraq. People are electing their leaders for the first time in generations, or ever, in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya. The United States and our partners built a broad coalition to stop Qadhafi from massacring his people. And a ceasefire is holding in Gaza. All good things. But not nearly enough.

Ongoing turmoil in Egypt and Libya point to the difficulties of unifying fractured countries and building credible democratic institutions. The impasse between Israel and the Palestinians shows little sign of easing. In Syria, the Assad regime continues to slaughter its people and incite intercommunal conflict. Iran is pursuing its nuclear ambitions and sponsoring violent extremists across the globe. And we continue to face real terrorist threats from Yemen and North Africa.

So I will not stand here and pretend that the United States has all the solutions to these problems. We do not. But we are clear about the future we seek for the region and its peoples. We want to see a region at peace with itself and the world – where people live in dignity, not dictatorships, where entrepreneurship thrives, not extremism. And there is no doubt that getting to that future will be difficult and will require every single tool in our toolkit.

Because you can’t have true peace in the Middle East without addressing both the active conflicts and the underlying causes. You can’t have true justice unless the rights of all citizens are respected, including women and minorities. You can’t have the prosperity or opportunity that should be available unless there’s a vibrant private sector and good governance.

And of this I’m sure: you can’t have true stability and security unless leaders start leading; unless countries start opening their economies and societies, not shutting off the internet or undermining democracy; investing in their people’s creativity, not fomenting their rage; building schools, not burning them. There is no dignity in that and there is no future in it either.

Now, there is no question that everything I’ve discussed and all that I left off this set of remarks adds up to a very big challenge that requires America to adapt to these new realities of global power and influence in order to maintain our leadership. But this is also an enormous opportunity. The United States is uniquely positioned in this changing landscape.

The things that make us who we are as a nation – our openness and innovation, our diversity, our devotion to human rights and democracy – are beautifully matched to the demands of this era and this interdependent world. So as we look to the next four years and beyond, we have to keep pushing forward on this agenda, consolidate our engagement in the Asia Pacific without taking our eyes off the Middle East and North Africa; keep working to curb the spread of deadly weapons, especially in Iran and North Korea; effectively manage the end of our combat mission in Afghanistan without losing focus on al-Qaida and its affiliates; pursue a far-ranging economic agenda that sweeps from Asia to Latin America to Europe.

And keep looking for the next Burmas. They’re not yet at a position where we can all applaud, but which has begun a process of opening. Capitalize on our domestic energy renewal and intensify our efforts on climate change, and then take on emerging issues like cyber security, not just across the government but across our society.

You know why we have to do all of this? Because we are the indispensable nation. We are the force for progress, prosperity and peace. And because we have to get it right for ourselves. Leadership is not a birthright. It has to be earned by each new generation. The reservoirs of goodwill we built around the world during the 20th century will not last forever. In fact, in some places, they are already dangerously depleted. New generations of young people do not remember GIs liberating their countries or Americans saving millions of lives from hunger and disease. We need to introduce ourselves to them anew, and one of the ways we do that is by looking at and focusing on and working on those issues that matter most to their lives and futures.

So because the United States is still the only country that has the reach and resolve to rally disparate nations and peoples together to solve problems on a global scale, we cannot shirk that responsibility. Our ability to convene and connect is unparalleled, and so is our ability to act alone whenever necessary.

So when I say we are truly the indispensible nation, it’s not meant as a boast or an empty slogan. It’s a recognition of our role and our responsibilities. That’s why all the declinists are dead wrong. (Laughter.) It’s why the United States must and will continue to lead in this century even as we lead in new ways. And we know leadership has its costs. We know it comes with risks and can require great sacrifice. We’ve seen that painfully again in recent months. But leadership is also an honor, one that Chris Stevens and his colleagues in Benghazi embodied. And we must always strive to be worthy of that honor.

That sacred charge has been my north star every day that I’ve served as Secretary of State. And it’s been an enormous privilege to lead to the men and women of the State Department and USAID, nearly 70,000 serving here in Washington and in more than 270 posts around the world. They get up and go to work every day, often in frustrating, difficult, and dangerous circumstances, because they believe, as we believe, that the United States is the most extraordinary force for peace and progress the world has ever known.

And so today, after four years in this job, traveling nearly a million miles and visiting 112 countries, my faith in our nation is even stronger, and my confidence in our future is as well. I know what it’s like when that blue and white airplane emblazoned with the words “United States of America” touches down in some far-off capital and I get to feel the great honor and responsibility it is to represent the world’s indispensable nation. I’m confident that my successor and his successors and all who serve in the position that I’ve been so privileged to hold will continue to lead in this century just as we did in the last – smartly, tirelessly, courageously – to make the world more peaceful, more safe, more prosperous, more free. And for that, I am very grateful.

Thank you. (Applause.)

MR. HAASS: Well, thank you, Madam Secretary.

SECRETARY CLINTON: Thank you.

MR. HAASS: Both for what you had to say as well as for the last four years. Let me just take advantage of my position and ask the first question.

You gave an extraordinarily comprehensive talk that touched on – I think you called them the many levers of American influence and power, and made the case for various forms of our power. So when it comes to putting it together, is there an Obama doctrine, is there a Clinton doctrine, that somehow ties together, gives a sense of priorities, helps explain what it is we should do and not do and how we should do it in the way that other doctrines historically have played that role?

SECRETARY CLINTON: Well, I think that, as you can tell from what I said, we believe that America must continue to be the indispensable nation and the global leader on behalf of peace, prosperity, and progress, and that that requires us not only to lead alone but also to build coalitions and networks that will put responsibility with others and expect them to play their role in a rules-based global order. So it’s not always easy to talk about what we are doing everyday everywhere in the world, but I think if you look at what we have done, we have certainly kept faith with that kind of mission.

MR. HAASS: I will show uncharacteristic self-restraint – (laughter) – as those of you who know me, and we’ll try to have time for a couple questions. Yes, ma’am, all the way in the back. Yeah, right there. Just wait for the microphone and just let us know who you are.

QUESTION: Thank you. My name is Nadia Bilbassy, I’m with MBC Television, Middle East Broadcasting Center. Madam Secretary, some of the successes that have been attributed to you is mending or fixing United States relation with the Arab and Muslim world. Yet the statistics contradict that. If you look at the Pew statistics, it shows that actually your favoritism in comparison to the Bush Administration is lower, and in countries like Turkey, Jordan, and in other places. So what is going wrong? Does that mean that America’s stand in the world is on the receding end, that its prestige has been affected? Thank you.

SECRETARY CLINTON: Let me say three things about that. First, I have obviously followed closely public opinion, and I think it’s fair to say that the United States, for the last decade, has not been viewed favorably by a very high percentage of the people in any of the countries in the Middle East or North Africa for a number of reasons, some of it rooted, of course, in our strong support for Israel over the many years of Israel’s existence as a state.

So this is not the Obama Administration, the Bush Administration, the Clinton Administration. This is the views of many people in the region about America. And I think it’s unfortunate because clearly what the United States stands for is absolutely in line with what the Arab revolutions have been publicly espousing.

Secondly, I think that we have done – and I take responsibility, along with our entire government and Congress and perhaps our private sector – we have not done a very good job in recent years reaching out in a public media way or in a culturally effective way to explain ourselves. I’m always encountering so many conspiracy theories that are totally off-base, wild, made-up stuff that the media in the region promotes about the United States that is absolutely untrue. Our response has been: Nobody will either believe it, or we can’t possibly contest it.

I take a different view. I think we ought to be in there every single day. I made a point of reaching out to Al Jazeera when I became Secretary of State because it was unrelentlessly – or was relentlessly negative about us. And I said, “Come on. That is not only inaccurate, but it’s deeply unfair.” And their response to me was, “Well, your government never puts anybody on Al Jazeera.” I said, “Well, that’s going to change right now.” You can’t be in the arena and expect there to be a change if you’re not willing to get off the bench. And from my perspective, that’s our fault. We have let a lot of stuff be said about us, believed about us that is contrary to who we are as a people, what we stand for, and what we’ve done.

I guess thirdly, we, in our efforts to support democracy, still are held accountable for supporting the governments that were there before democracy. You deal with governments of all kinds. We deal with China. Hardly anybody believes that China fully respects human rights, and it certainly is not a democracy. But we don’t get blamed because we do business with China, but we did business with other regimes and somehow that caused lasting negativity toward us, which I think, again, is unfounded.

So there are reasons for all of the points that you made that go more to the heart of American foreign policy and American values, but we can do a better job in at least disabusing and refuting some of what people are led to believe that is contrary to who we are.

MR. HAASS: Allan Wendt.

QUESTION: Allan Wendt, formerly with the State Department. Madam Secretary, you’ve outlined a very ambitious agenda and program of work for the Department of State. Could you tell us a little bit about the budgetary resources that will be required to carry out that agenda? (Laughter.)

SECRETARY CLINTON: Well --

MR. HAASS: I bet you’re glad he’s asked that question.

SECRETARY CLINTON: I’m very glad he asked that question. We’ve had some success in the very first years of my tenure in making the case to the Congress to increase our budgets, increase our workforce to be able to deal with the myriad of challenges, threats, and opportunities we face. But we are moving into the budget negotiations and a potential sequestration, which will be disastrous. And people will focus, and they should, on what sequestration will mean to the military. Hundreds of thousands, maybe 800,000 civilians will lose their jobs. Bases will have to be closed. Programs will have to be stopped. So the Defense Department will be able, if anyone’s willing to listen, say, “Look, here’s what the immediate effect will be,” and it won’t only be about our military might, it’ll be about the economy.

You saw in the 4th quarter slowdown one of the reasons was decreased military spending as people hedge against and get prepared for this absurd sequestration idea. In the State Department, we can’t look at military programs that are producing weapons, but we can look at people being furloughed, which they will. We can look at cutting back, once again, on security, which has been one of the challenges we have inherited over the years, and which I tried to explain to the Congress. We can look at the cutbacks in passports that the American people deserve us to provide, and on and on and on.

So although we are one-twelfth, one-thirteenth of the Defense Department budget, what we do does directly affect Americans. It’s not just programs over there, it’s what happens here at home and what we do through those programs and posts that make it possible for us to have jobs and travel easily and so much else. So I thank you for asking it. This is a government-wide challenge and something that no great country should do. I mean, just as a final note, I was giving a speech in Hong Kong during the last debt ceiling debate, and all these very sophisticated investors and government officials lined up to say, “Is the United States really going to default on its credit?” And I said, “Oh, no, no, no. We’ll never do that.” Oh lord, please be – (laughter). So are we really going to have mindless sequestration? Are we really going to, in effect, handicap ourselves? We’ll see. I hope not. I hope that cooler and smarter heads prevail.

MR. HAASS: Want to do one or two more?

SECRETARY CLINTON: Sure. Sure.

MR. HAASS: Okay. Diana.

QUESTION: Diana Lady Dougan, Center for Strategic and International Studies and Cybercentury Forum. Madam Secretary, I think all of us are – want to say how honored we are to have had you as our Secretary, but I will move quickly on to a question that for those of us, particularly who served during the Cold War, it was much easier to identify American interests, and we had much more of a moral compass. And now I would like to know when you are talking about protecting and advancing American interests, is becoming more and more difficult and more and more parochial in identifying American interests, particularly in a transnational world and the various vested interest groups. So what advice do you have to give to your successors in terms of defining American interests and redefining them?

SECRETARY CLINTON: Well, that’s an excellent question and I think it’s on two levels. On the most fundamental level, protecting America and Americans has to remain a core interest. Our security is nonnegotiable, and we have to be smart about what really threatens us and what doesn’t. We have to work better on intelligence so that we don’t make very unfortunate mistakes. So but security first and foremost, and I don’t think any official Secretary of State or otherwise could put anything before that.

Secondly, we need an open, transparent free market in which Americans are able to compete on a level playing field. Because when we can compete, we often can win. But the deck has been stacked against us in the last years because of all kinds of forces converging, whether it’s state-owned enterprises or indigenous protections that are behind the borders and so forth. So it is very much in our interest to help write the rules for the 21st century global economy, and then to think of mechanisms to enforce those rules.

Thirdly, we have to continue to advance American values, which correspond with universal values. I’m always reminding my counterparts that when I talk about freedom of expression, freedom of religion, those are not just American values. The world agreed to those values back in the declaration, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. And we’re going to stand up for them, and it’s not always easy and we have to pick our times. We can’t be shortsighted or counterproductive, but we’re going to continue to stand up for them. So on the fundamental first level, we do what we do because it’s in our security interest, our economic interest, and our moral interest, and we have to continue to do that.

But then, as you go up to sort of the second level, how you adapt that to the world of today, requires us to be more clever, more agile, and we’re trying to do that. So, for example, countering violent extremism, there are those who estimate that maybe there are 50,000 violent, homicidal extremists in the world, but they are able to maximize their impact and their messaging through the internet. And what we have tried to do, as I briefly mentioned, is to get in there with them, to undermine them, and to rebut them. It is something we did quite well in the Cold War.

The more I’ve done this job, the more lessons I think we can transfer from the Cold War to today. No, we don’t have some monolithic, Communist Soviet Union. But we were engaged minute by minute in pushing out our ideas, our values, refuting Communist propaganda. Cold War ended, people said, “Oh, my goodness, thank the lord, democracy has triumphed, we don’t have to do any of that anymore.” That is a terrible mistake. We have basically abdicated, in my views, the broadcast media. I have tried and will continue from the outside to try to convince Congress and others, if we don’t have an up-to-date, modern, effective broadcasting board of governors, we shouldn’t have one at all.

Other countries, Russia, China, and I mentioned Al Jazeera already, they have government messaging that is now predominant in so many places in the languages of the places. And we transport our culture and entertainment around the world, which doesn’t always unfortunately convey our best values – (laughter) – but we abdicate in really investing in and modernizing what our broadcasting potential could be.

So I think there are many more examples, but I would say that if you look at how successful we were in the Cold War – thankfully we never went to war with the Soviet Union, we never stopped negotiating with the Soviet Union, and we engaged in a lot of very sophisticated diplomacy around the world, and we did things like support certain people in elections because they were more democratic than other people. I mean, we did a lot.

I mean, George Shultz was here the other day and we did so much to kind of help those who were on the side of democracy and freedom survive behind the Iron Curtain and then thrive when the Iron Curtain fell. And I have a long list of things that I would love to see us doing in a modern way that we have not yet adapted to this new time.

MR. HAASS: Time for one last one. Yes, Ma’am. (Inaudible.) Just wait for the microphone.

QUESTION: Thank you. Ricki Tigert Helfer, Financial Regulation Reform International. Immigration reform has been seen as largely a domestic issue, but I would like very much for you to give us your views on to what extent immigration reform will enhance our ability to deal with other countries and to foster U.S. values abroad.

SECRETARY CLINTON: Well, it’s funny. My very last bilateral meeting was with, yesterday, the new Foreign Secretary of Mexico. And we talked about the benefits to both United States and Mexico, in fact, all of North America and better integrating our economies, our infrastructure, our energy, particularly our electricity grid and so much else that is possible.

So immigration reform is the right thing to do for America and for people who are here who have, in many instances, been here for a very long time, made their contributions to this country, have been law-abiding, contributing residents. But it’s also to our benefit with our neighbors to the south. What’s happened in the last several years has been actually a slowing down of immigration – undocumented immigration from Mexico, because as our economy was struggling and jobs were not as available, and the Mexican economy was growing, people didn’t come or they went home. So now much of the immigration flows are coming from further south, from countries where there is still a lot of instability and very significant poverty.

So what we have to do is have, as the President said, comprehensive immigration reform, which means not only border security on our borders, but helping with border security further south so that we can then move on to dealing with the 11 million-plus people who are here and creating some path to citizenship. That will be a huge benefit to us in the region, not just in Mexico, but further south. At the same time that we do immigration reform, we need to do more on border security and internal security in Central America.

We should be very proud of the role we played in stabilizing Colombia from the drug cartels and the FARC rebels, and we’ve made a lot of progress with Mexico under the Merida Initiative. But the result, that these Central American countries are increasingly squeezed. So their internal workforce will not have many opportunities once we do immigration reform, once the Mexicans get serious about their border. Then I think we have to do more with the Central American countries in order to help them the way that we have helped others.

MR. HAASS: Madam Secretary, you spoke about the indispensability of American leadership and how the world would be, I think, a much worse place were it not for such an active American role. But coming back to immigration reform and to your comments about sequestration, are you optimistic about the capacity of the American political system to come up with policies that will allow us to sustain that kind of American leadership?

SECRETARY CLINTON: Absolutely. I mean, if you look back, we’ve done some really stupid things. (Laughter.) And over 200 years we’ve passed terrible laws. We’ve had all kinds of government-sponsored or condoned discrimination against all kinds of people. We’ve made our mistakes. We may be indispensible; it doesn’t mean we’re perfect. We’re probably as close to perfect as anybody has been – (laughter) – but (inaudible). We’re maybe not there yet, but we’re still trying to form a more perfect union.

But no, I think – look, you look at the sweep of American history, and sometimes it takes longer than it should, but eventually we do overcome our own discriminatory tendencies, our own insecurities and fears, and I have no doubt that we will again. It is distressing when you’re watching some of what is happening, but I think you have to take a longer view. And certainly in my view, that’s one for optimism.

MR. HAASS: At the risk of leaving you all with an image that probably isn’t good, I would simply say that John Kerry has some fairly large Manolo Blahniks to fill. (Laughter.) I want to thank the Secretary of State again for everything she’s done. (Laughter and applause.)

###